Why Rollapadu Wildlife Sanctuary?

Rollapadu is a crucial grassland sanctuary, protecting the Great Indian Bustard, Lesser Florican, and other birds through grazing-free enclosures.

Critically Endangered

IUCN Red List Status

<200 Birds

Current population in India

Since 2016

Bustard Recovery Program

Historical Background

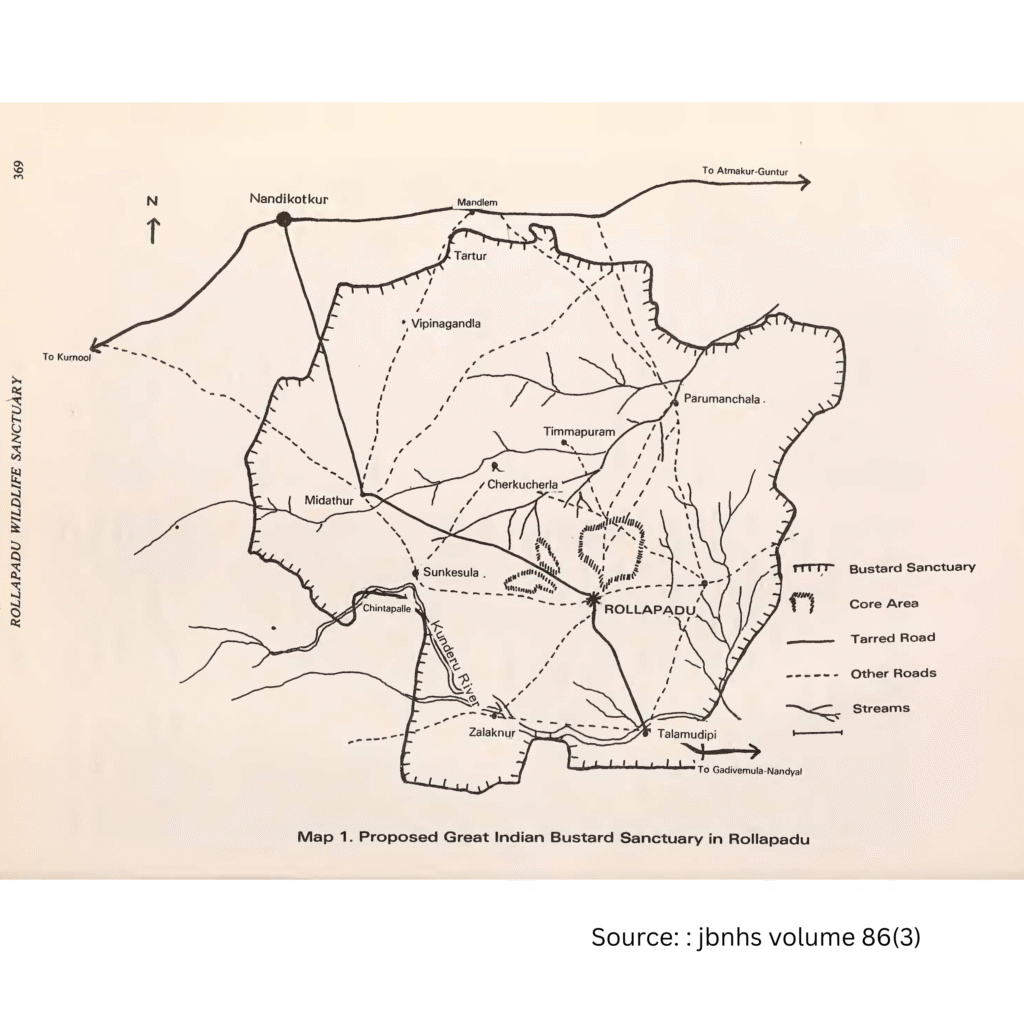

Source: Journal of Bombay Natural History Society, Vol.86.

The Rollapadu Wildlife Sanctuary in Andhra Pradesh—formally notified in April 1988 following Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) recommendations—became the state’s best-known refuge for the Great Indian Bustard (Ardeotis nigriceps). BNHS maintained a field station at Rollapadu from September 1985 to May 1988 to document baseline ecology of the sanctuary and its fauna and flora, with special emphasis on the bustard. Rollapadu lies 18 km southeast of Nandikotkur, on the Kurnool–Cuddapah formations, with gravelly, clay-rich soils; black-cotton soils occur nearby. Climate is hot and semi-arid: April–May temperatures peak near 42 °C, winter is mild (December ≈18 °C), and average annual rainfall is ~667.8 mm from both SW and NE monsoons; late-April dust storms bring brief showers.

The sanctuary covers 614 ha split into three fenced enclosures (trench-cum-mound walls) with controlled access roads that double as firebreaks, plus a waterhole. People and livestock are excluded from the core, yet traditional right-of-way roads are retained to reduce local antagonism. Vegetation represents degraded Tropical Thorn Forest, now a grassland mosaic with scattered shrubs/trees. Dominant grasses include Aristida funiculata, Chrysopogon fulvus, Eremopogon foveolatus, Heteropogon contortus (noted to spread between 1985–1987, overrunning an earlier E. foveolatus nesting patch), and Iseilema anthephoroides. Monsoon ephemerals flush June–December. Inside the enclosures, protection from grazing/woodcutting has yielded taller, denser grasses (>50 cm) and even pure stands of Sehima nervosum—absent from surrounding overgrazed lands—hinting at a potential Sehima/Dichanthium climax if protection persists.

Historically, bustards were known from the “dry districts” of Andhra Pradesh, but contemporary knowledge was scant until 1982 rediscoveries around Rollapadu and nearby sites; a record flock of 35 was seen in July 1984. Hunting (earlier via nooses at display sites, groundnut fields, and waterholes) declined sharply after sanctuary staffing began. Based on daily counts, flocks, and nest finds, the local population was estimated at ~60–100 birds, though movements complicate precise census. Seasonal dynamics are pronounced: with the SW monsoon (June–August) birds congregate and flock sizes peak; sexes generally segregate and mixed flocks are rare. From mid-August, a major breeding season begins (eggs laid until January), followed by widespread solitariness and territoriality; a minor breeding season occurs with April–May pre-monsoon showers. Courtship displays were often dominated by a single territorial male at traditional leks (“Meeta Male”), though territorial turnover was reported by trappers and multiple territories occurred in 1987, underscoring the need for long-term studies on marked birds.

Other notable fauna include: Lesser Florican (Sypheotides indica) with a surprising spate of local display/nesting in late 1987–early 1988 (possibly tied to rainfall failures in core northern grounds or NE-monsoon breeding); large winter influxes of Demoiselle Cranes (peak Jan–Feb; crop depredation issues), Bar-headed Geese (numbers variable), White Storks (regular, smaller flocks), and Black Storks (regular south to ~15° N). Rollapadu also supports significant winter roosts of Montagu’s and Pallid Harriers (~1,000 at peak). Blackbuck rose from ~17 (1985) to ~35–40 (1988); wolves bred repeatedly, while foxes were scarce and jungle cats reported.

Given the tiny, fragmented 614-ha core and wide ranging of bustards, the authors urge adding multiple cores and a formally managed buffer of at least ~200 km² around Rollapadu, with strict oversight of land-use change, and extending habitat protection and staffing to other Andhra bustard locales (e.g., Banganapalle, Hanimireddypalli), lest gains at Rollapadu be undermined by declines elsewhere.

Why Rollapadu

A Sanctuary Built for the Bustard

Rollapadu Wildlife Sanctuary was created specifically to protect the Great Indian Bustard and the precious Deccan grasslands ecosystem. We propose to work closely with the Andhra Pradesh Forest Department, BNHS, WII and other scientific bodies & local communities to transform this sanctuary—and the working landscape around it—into a thriving habitat for ground-nesting birds, blackbuck, harriers, and other grassland specialists.

Protected Status

Dedicated wildlife sanctuary with legal protection for GIB habitat

Community Partnership

Working with local communities for sustainable co-existence

Ecosystem Approach

Protecting entire grassland ecosystem and multiple species

Strategic Location

Key habitat in the Deccan grasslands with proven GIB presence

Our Plan: The Rollapadu Model

A comprehensive, science-based approach to bustard recovery that addresses immediate threats while building long-term habitat security.

Step 1

Protection:

Protection of the three enclosures within the sanctuary with high fencing. Presently, 10% of fencing is pending.

Step 2

Grasslands:

Common grass species were Aristida funiculata, chrysopogen fulvus, eremopogen fovoelatus in the 1980's. These grasses have to be restored.

Step 3

Translocation:

Bring young chicks from Rajasthan, acclamitize them to the harsh wildlife by creating an aviary.

Step 4

Breeding Centre :

For security reasons and virus attacks, a GIB breeding centre shall be established on the lines of Ramdevra

Step 5

Step 5 High Tension Power Lines :

Follow SC directions without jeopardising economic development. Instal bird diverters. Paint black colour on the blades of wind turbines.

Step 6

Former involvement :

Mixed cropping pattern, crops friendly to GIB, non use of chemical fertilisers & pesticides, stop future irrigation works, crop subsidy etc.

What Success Looks Like

Key Performance Indicators you can track on this site